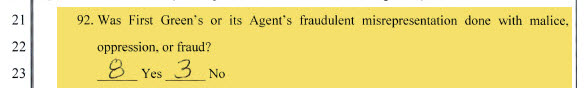

On June 29, 2023, the jury awarded Turner Law’s client punitive damages!

Punitive damages require proving that the defendant was guilty of malice, fraud, and/or oppression by clear and convincing evidence, a much higher burden of proof than the preponderance of the evidence standard used for most civil law claims.

Our client was brought into the case as a defendant in a cross-complaint. The plaintiff had borrowed $80,000 from a hard money lender. To summarize a long fact pattern, the hard money lender foreclosed and sold the plaintiff’s home in Brentwood for $4.5 million, netting approximately $1.5 million. Our client and plaintiff were in their 70s; they had been friends since they were high school in the 1960s. Our client had provided $10,000 to the lender and was supposed to receive 9.52% interest in the lender’s deed of trust. But instead of paying our client from the sales proceeds, a cross-complaint was filed against our client.

The case is still ongoing. On November 15, 2023, the judge awarded our client essentially 100% of the value of his 9.52% interest, which we calculated to be $149,879.27. There are a few remaining issues for the court to decide before the judgment is entered.

Keith Turner and Scott Humphrey tried the case.

More on punitive damages law: “Where the defendant’s oppression, fraud or malice has been proven by clear and convincing evidence, California law permits the recovery of punitive damages ‘for the sake of example and by way of punishing the defendant.’” Simon v. San Paolo U.S. Holding Co., Inc. (2005) 35 Cal.4th 1159, 1184 (quoting Civ.Code §3294(a).) The California Supreme Court has declared that the purpose of punitive damages is “to punish wrongdoing and thereby to protect [the public] from future misconduct, either by the same defendant or other potential wrongdoers.” Adams v. Murakami (1991) 54 Cal.3d 105, 110. “The purpose of punitive damages is to punish wrongdoers and thereby deter the commission of wrongful acts.” Neal v. Farmers Ins. Exchange (1978) 21 Cal.3d 910, 928, fn. 13 (citing Evans v. Gibson (1934) 220 Cal. 476; Fletcher v. Western National Life Ins. Co. (1970) 10 Cal.App.3d 376, 409.)

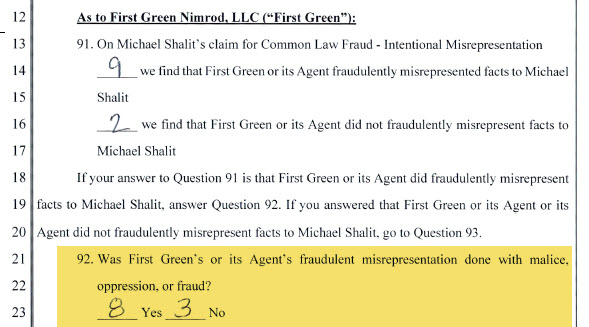

Because the jury was down to 11, 8 votes below were required to win: